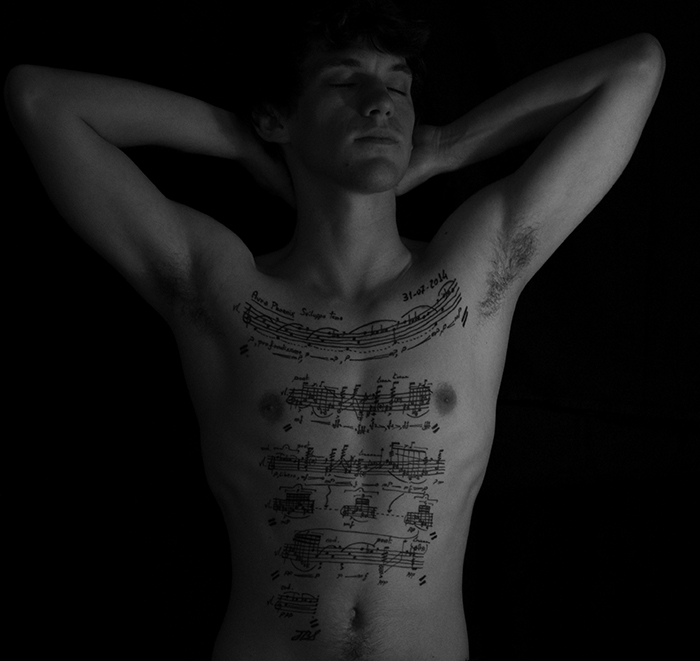

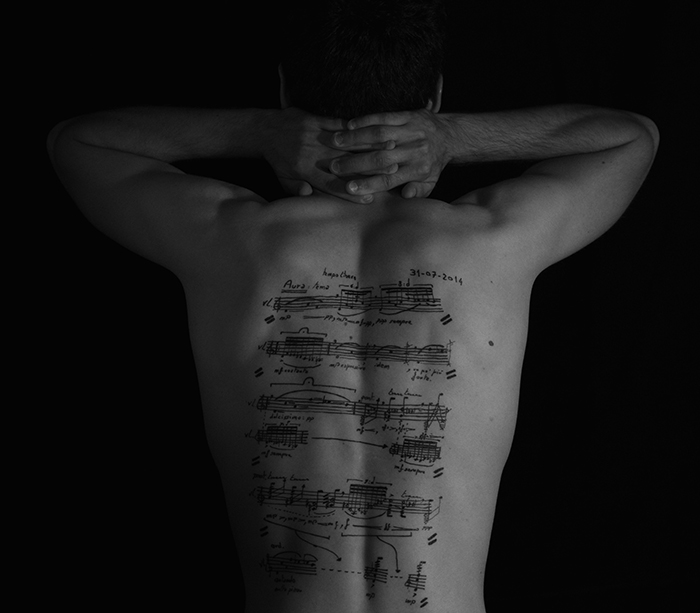

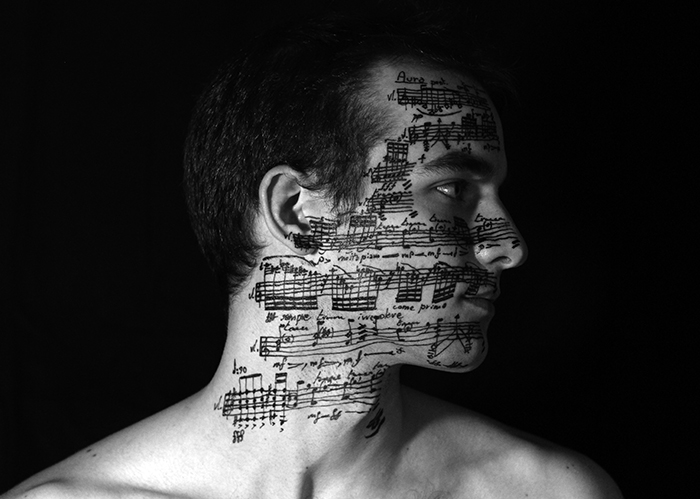

Conception - Jacopo Baboni Schilingi

The question in music of what is « to be seen » and what is « to be heard », in music is a fundamental question. For European music, the action of writing was more a strong constraint than a possibility of expression. Writing music pushed composers far from the sound intuitions into new complexity in controlling music ideas. It became « the » method of conceiving music. It seems that there is a contradiction: music has to be heard, but at the same time all the composers of the so called « erudite » music chose to write it in order better read it. Written music is not the only way of composing it of course, but the existence of scores is because one main reason: how to communicate several sound ideas through and to musicians.

These photos have been realized with Benjamin Parinaud in Paris (France)

Photo by Benjamin Parinaud

Music in your skin

By Philippe Langlois

Music is well and truly alive today. Through the various forms that it takes, so-called ‘contemporary’ music conveys in innumerable ways the dynamism and diversity of musical creation at the beginning of the 21st Century.

For composer Jacopo Schilingi, this living aspect of music is fundamental, even primordial. He concentrates on the here and now, the present, the very instant in which music is thought up, composed, where it is eventually played. He develops this very specific connection he has with living music, this ‘instantaneity’ is clear as he works on the various stages involved in composing, as he writes the score and his interpretation on stage, live. As well, he sometimes turns to digital music and processing sound in real time.

Being a composer is, above everything else, about having music ‘in your blood’, ‘in your bones’. It’s the feeling of music vibrating in your body, in an organic way, and to feel it in the very depths of your heart and soul. On the surface, you experience it as a shiver which runs all down your body, raising each goose bump, running all the way up your spine to the top of your hair, a ‘skin orgasm’ which only the emotion of music can cause.

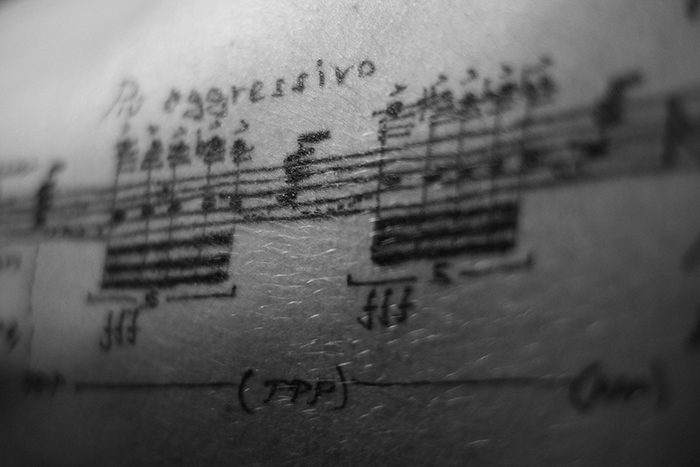

To anchor himself even more firmly to this particular link which the composer develops with ‘living music’, specifically with its memory, Jacopo Baboni Schilingi is attempting to literally reincarnate musical writing in the here and now, a way for him to fight against the perverse effects caused by the appearance of musical production computer programmes, which have, little by little, dematerialised and disincarnated it. These programmes, which emerged around the year 2000 have been used in a generalised way and have wiped out all traces of the art of musical calligraphy. Marks, notes and traces of ink were hidden by the ‘character police’, banishing the originality of calligraphy into the forgotten past. Previously, publishing houses would have published faxes of the original manuscripts. Musical writing has a duty to raise the art of calligraphy to the highest degrees of perfection. One only has to see manuscripts of scores written by Brian Ferneyhough, Ivan Fedele, or France Donatoni who, in this field, represent meticulously perfect models of this art.

Since 2007, Jacopo Baboni Schilingi has therefore tried to take up this art again, desiring to make calligraphy continue, in a very particular and personal way; through the revival of his practice of musical writing. Touched by the cinematic adaptation of the book by Sei Shonagon, Pillow book by Peter Greenaway in 1996, as well as Cinq femmes autour d'Utamaro by Kenji Mizoguchi (1946), he slowly began to write sketches of scores directly onto bodies, onto the living skin of models. He asks them to his studio, where in slots of six to twelve hours to compose, with a thin tip felt-pen on their backs, arms, faces, legs, chests, and patiently inks staves and music notes, a way of literally ‘incarnating’ the motion of writing on the living, a way to make sacred this action in this written form. In doing this, he reaffirms his attachment to traditional writing, abandoning the ‘character police’ in favour of calligraphy, which he carries out on the smooth skin of models he invites to his studio.

There is nothing more obvious than the body for speaking the truth about life, the envelope of the living, which is the skin, this living canvas upon which the memory of the past can be read. Thanks to the pre-eminence of the motion itself, the memory of writing is coming back to life in the same moment of living and of thought. To ink music onto the skin is also seeking to anchor again the living of creation from the writing stage.

Without any possibility of deleting or going back or being able to rip up the medium, mistakes are not allowed, or rather is has to be included and accepted in the written piece of music. It can be likened to a search for the perfection of a motion, or movement, like the fable of Italo Calvino, Rapidié, taken from Leçons américaines, in which is told the story of a Chinese Emperor who orders the best artist in the kingdom to draw the best picture of a crab, and who, after ten years of working, produces in one stroke, before a dumbfounded emperor, the outline of a crab in the perfection of a motion which has been repeated over and over again.