Bodyscore project exists across different kind of monstration: books of photography, photo exhibitions in art galleries or art centres, live performances during which scores are painted lively, concerts where scores are projected on stage while musicians are playing.

There are countless photographs of musicians: singers, violinists, pianists, percussionists, guitarists, or conductors. Their faces, facial expressions, their tense bodies… Or the musical instruments, with or without the musicians. It may seem that nothing new can exist in the relationship between music and photography. But despite this, one questions remains unanswered: what are these musicians playing? Is it possible to take into account, via photography, the deepest nature of music, its composition? The musical score.

The score is a codified link, written by hand, which indicates how to embody the emotions that the composer expresses through his creation.

Today, musical scores are generated by software, which allows the musical transcriptions to be printed and distributed, directly. Therefore the “original” notation is in fact already an automated product. Before the advent of such tools, scores were hand written by composers, and the calligraphic excellence required was part of their stringent training. As with any precise, concentrated work, writing scores by hand demands long, intense labor. With time, a composer’s handwriting becomes a style, part of their personal signature, which corresponds to their sensibility. This is the school of composition in which Jacopo Baboni Schilingi was trained.

Writing by hand is not only a necessary process for basic learning, but – as we now know – the gesture of writing links vision and touch; or, more precisely: the brain simulates the movement before the act of writing. Accordingly, moving the hand is not the same process as calling forth a letter (or a note) on a screen. In other words, cognitive structures are a function of physical activity. Therefore it is logical that the mechanics of writing should transform the resulting text.

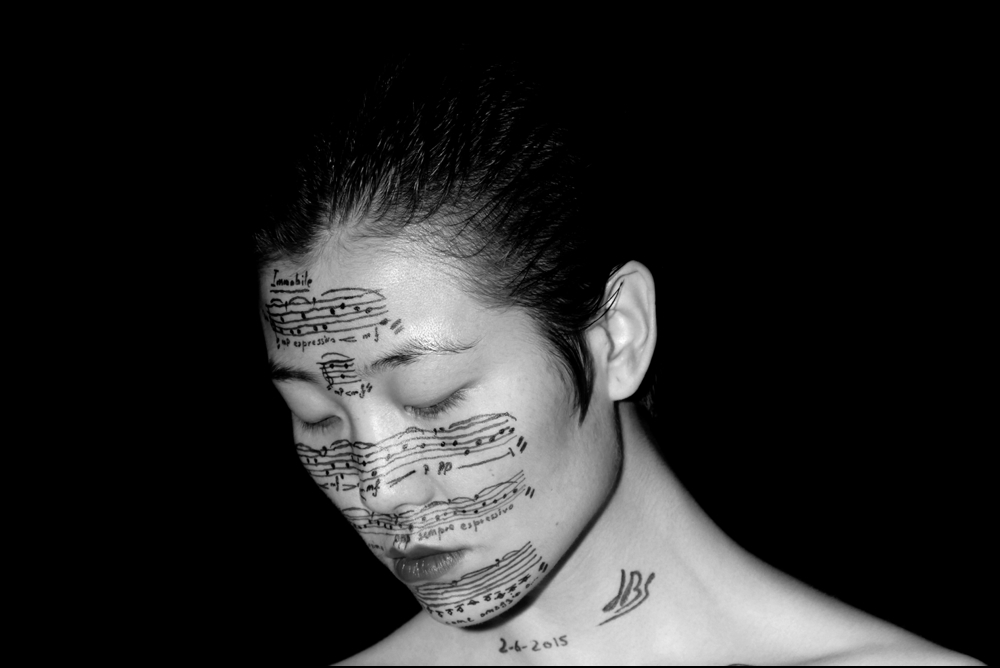

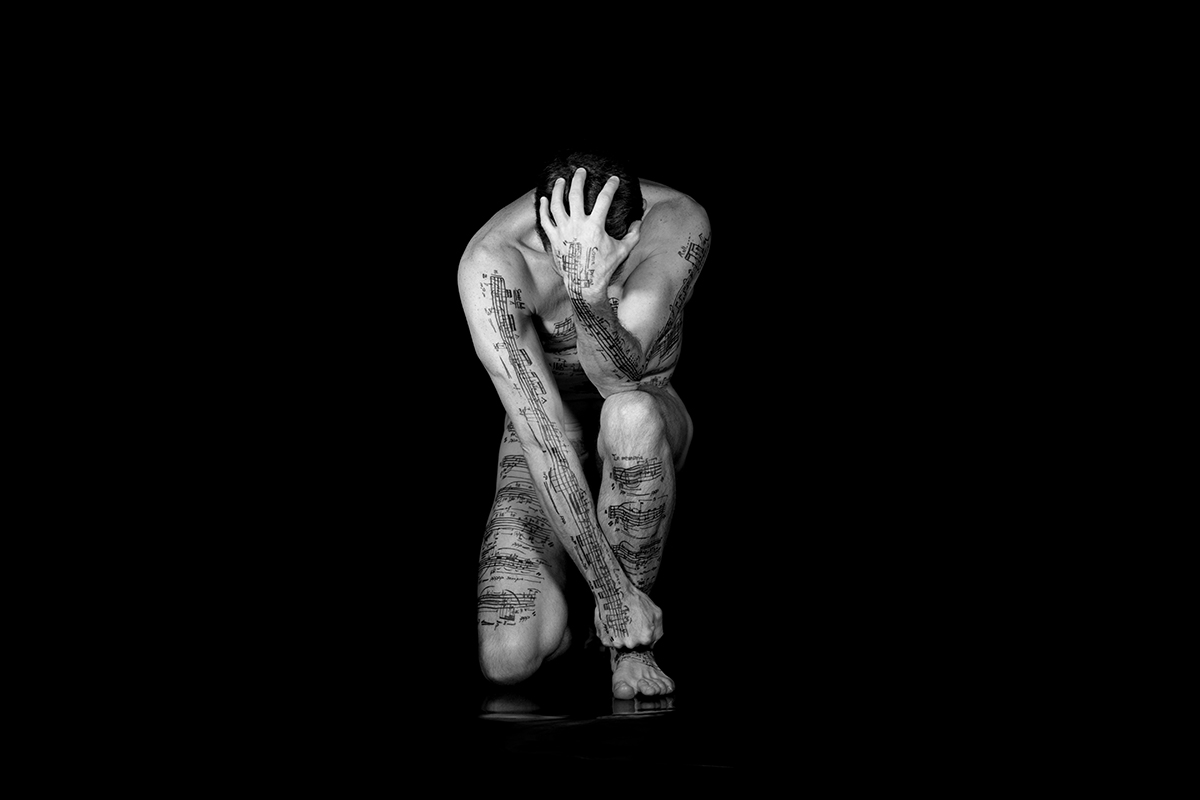

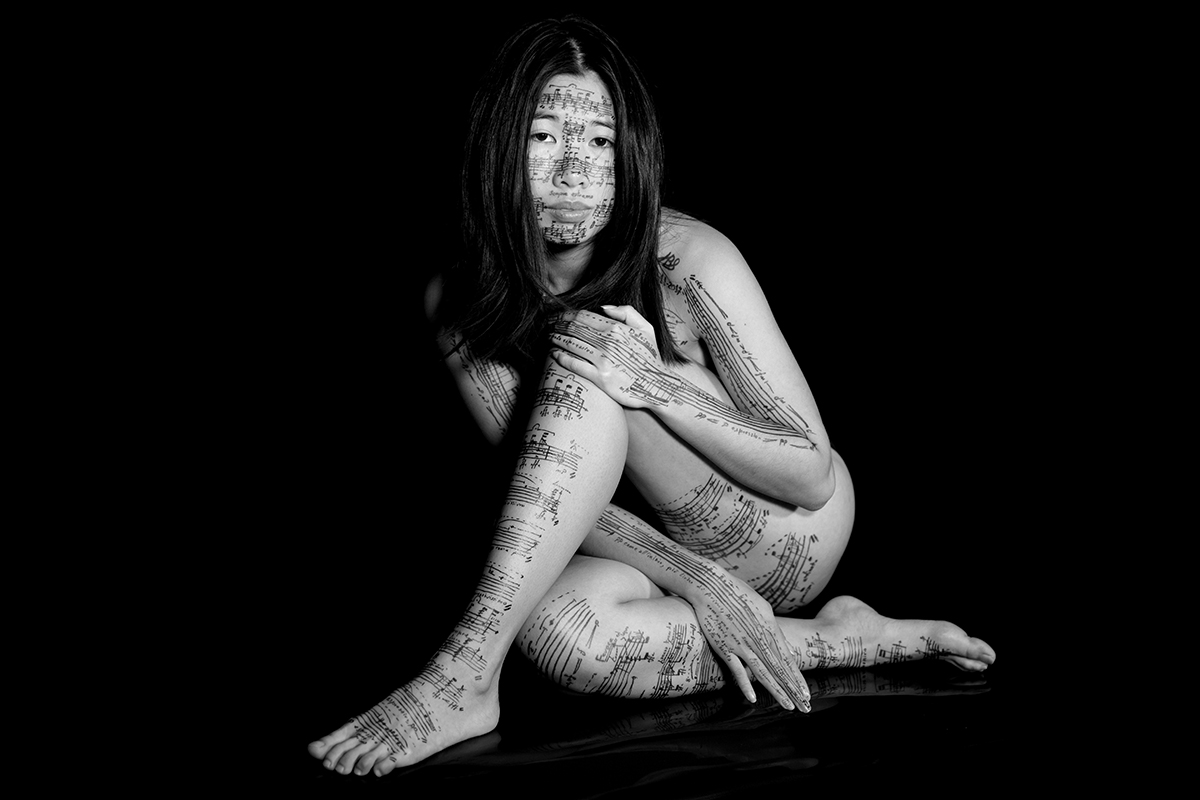

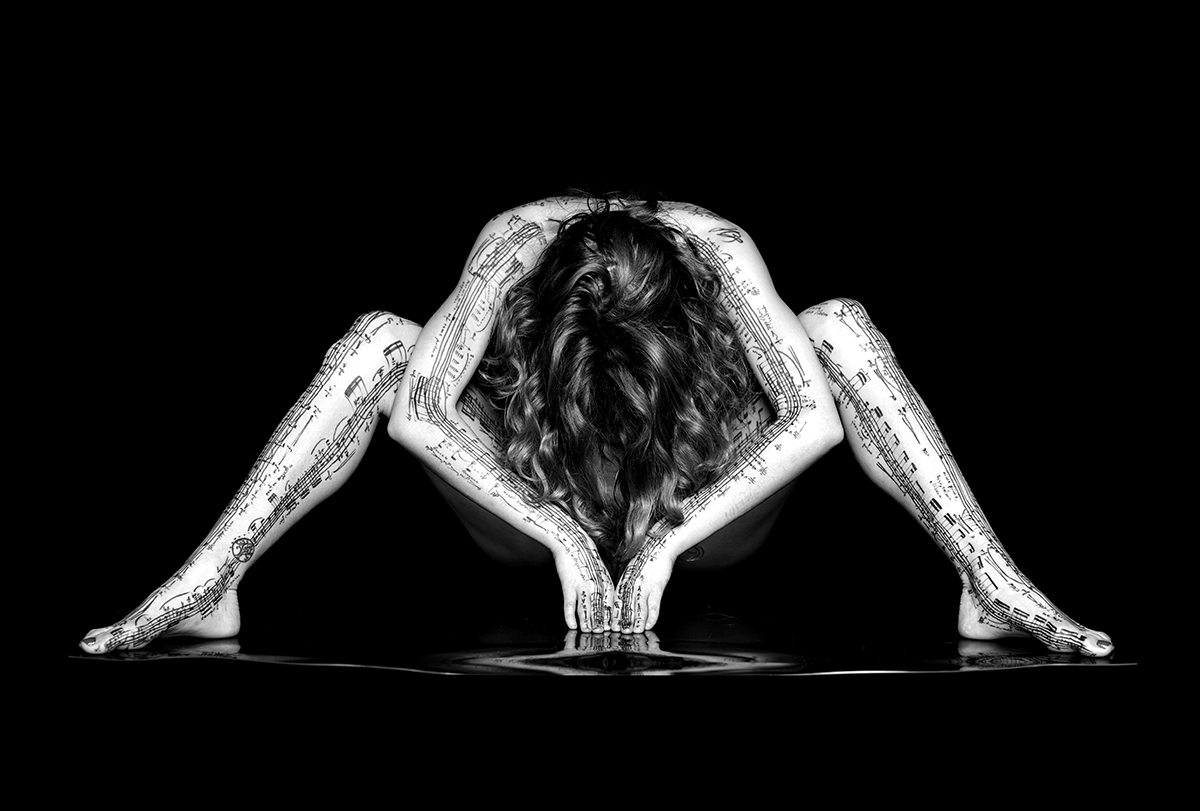

Since 2007, Jacopo Baboni Schilingi modified his compositional method to rediscover a “sculptural” sensibility, which had previously been altered by machines, via living materials, indispensable for creation. His choice is drastic, emphatic and powerful, as it represents – literally – a return to the body, a carnal return: his scores are henceforth not just written by hand, but also written directly onto human bodies. In his studio, converted into both a calligraphy atelier and photography studio, he collaborates with male and female models, who serve as living canvases for his compositions.

Body Score by Jacopo Baboni Schilingi

A few months ago, I tore up a sheet of music. The gesture had disappeared from my life and practice, for years now. For a friend’s birthday, I wanted to give him a handwritten copy of a composition he loves. But after a setback, I tore up the score. Tearing up something that you spent hours – even days – writing by hand is a brutal gesture. It is a final act. Tearing up a page leaves an indelible scar, one so deep that it becomes necessary to throw the page away. The act is violent, even theatrical.

For two years now I have asked myself fundamental questions about my work. Of course, I am a composer; I write and practice music. But I’ve been reflecting about how I go about it, via the writing process. I am becoming more and more interested in what it means to write music today, in 2015, and about the “old” way of experiencing music, via handwritten scores. Especially today, when almost everything is digital: computers, touch screens, networks, sensors…

Let’s compare the act of tearing up a sheet of music to “deleting” music from a hard drive. What a huge difference! There is nothing more ephemeral than the gesture of erasing a file from a computer. Click and delete. It’s gone! Such bravery! How heroic. Especially when we know that we can simply click “undo” to retrieve the file… Because the text displayed on the computer has not really been written. It was “typed.” Yuck! To “type a text” is not a very noble expression. Thus, I question my art. The music. Writing, composition. I belong to a generation of composers known as the “pen/mouse” generation: we know how to write for orchestra, string quartet, and voice, etc. on paper, but for concerts where electronics and information technology is ubiquitous. I compose music referred to as “mixed” and “interactive,” in which classical performers (pianists, violinists, oboists, opera singers, etc.) are on stage, and read and study music on paper, but who interact with computers during performances. This is the kind of music that I like. It suits me best. Faced with the possibilities, it is what I freely choose.

But (…and there is a but), from the age of 6 until 1999 (when I was 28), I composed by hand, on paper. The role of my publisher was limited to photocopying the scores, which needed to be written clearly enough to be read by musicians. Essentially, my publisher photocopied my manuscripts and distributed them to musicians. So I had to learn to write my music neatly, in terms of calligraphy, or it would not be played. To teach me how to write well, my mentor made me rewrite my first publically performed piece four times before delivering it to the performers. Not because of the musical content, but because of the calligraphy. I was 15. I was compelled to develop my own penmanship.

Writing changes over time. It grows with age and experience. As in any calligraphy, each gesture is the vehicle of the mood and the mental state of the artist. The score written by hand is the trace of the artist/composer, who is expressing himself; beyond the musical content, the score manifests the emotional state of the composer. Up until 1999, scores needed to be handwritten well so they could be read and performed live. The term speaks for itself: musical calligraphy. Beautiful music-writing. When writing by hand, it is necessary to be very focused to ensure the quality of the work and the visual quality within a given format. My teacher always told me, “Clarity of writing [reflects] clarity of mind.” Therefore, expectations were high. When writing by hand, an error, a crossing-out, an erasure, or starting over all cost a lot of time. Therefore we focus intently, so that even if mistakes can happen, we aspire to remain in the creative flow for hours at a time. It is a kind of psychic extension of being fully in the present, which the artist/composer knows so well. A state of concentration approaching trance, autohypnosis. Nothing exists but the music surrounding the artist. Time is suspended, but not in the way people often think. It is a time so accelerated that it seems as if the composer is paralyzed. In the pure enjoyment of the act of writing the sound, the artist/composer finds himself composing for hours without perceiving effort, fatigue, or any other concerns other than the writing itself. Because there is only the mental simulation of the music that will be played. A form of pleasure in preview, which only the composer knows, prepares, and plans.

Since the advent of music notation, scores have always aroused the utmost respect in musicians and non-musicians alike. Because for musicians the written score produces a sense in itself (a musical sense); for non-musicians the score represents the complex link between the imagination of an aural idea and the expression of this idea through others (performers), before they have even read the music. For non-musicians, the musical score is a kind of indecipherable letter, teeming with secrets. They are written, stripped bare, and yet unreadable. And while remaining indecipherable to non-musicians, the score is immediately recognizable as music by everyone, including those who don’t know how to read it. The score is the privileged medium between composer and interpreter.

The score is a codified link, written by hand, which indicates how to embody the emotions that the composer expresses through his creation. In his imagined potential; in his life; in his utopian possibility of existence: communication. And at the same time, through the only concrete reality of existence: music.

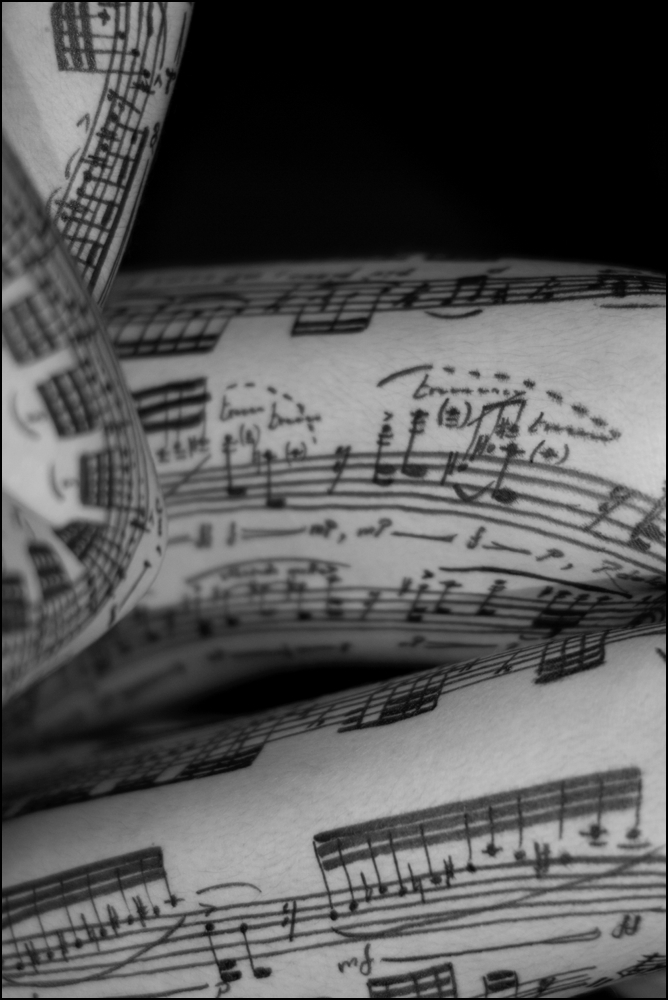

Of course, within a score we write notes and many other symbols, and these are the musician’s instructions. But a score is even more: it is a physical body on which the composer writes by hand, corrects, highlights, and erases, leaving all kinds of traces. At the same time, the score must be incomplete enough so that the performers can complete it with their own intentions and interpretations. And each interpreter – on the same score – adds new signs and symbols that will help them adapt to the composer’s intentions.

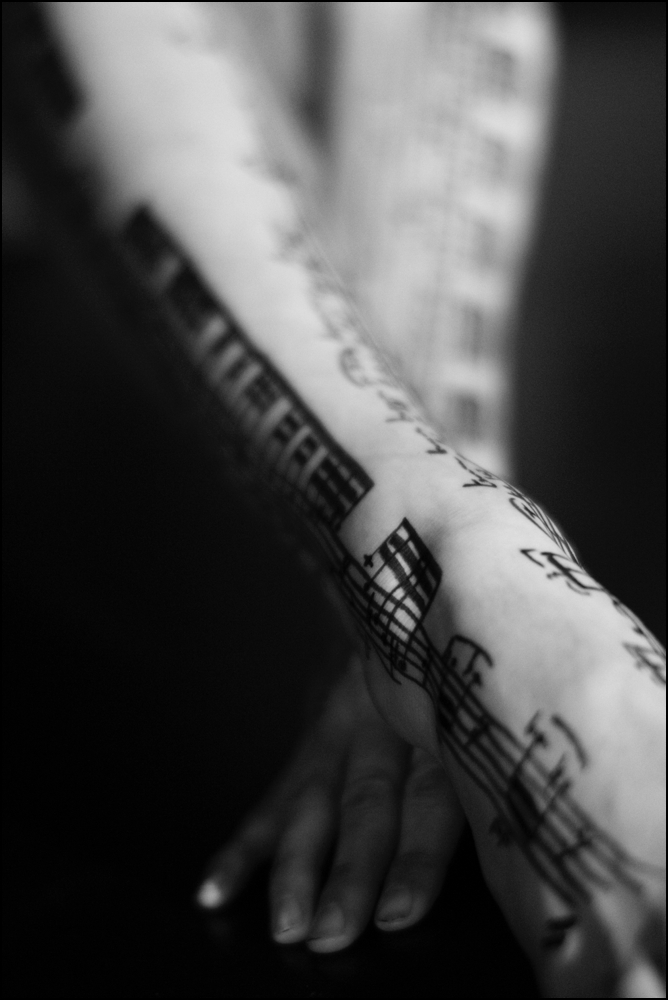

The score is the medium in which the interpreter can read the composer’s emotions, codified in the form of musical writing. Thus, the emotions of the composer are entrusted to the performers so they can relay them to the public via their musical instruments’ gestures. In a score, there are not just musical notes; for the musicians, these symbols imply hand, mouth and lip positions, feet movements, ways to use their bodies, and ways to move with the score’s aforementioned instructions.

A sensual relationship is undeniably established.

Movements, breathing, hesitations, uncertainties, impulses, efforts, tensions, relaxations, breathing, more breathing, how to breath, how to move, when to stay still. Softly, unhurried, crescendo, accelerando, pause. Breathe. Repeat from the beginning, slow down; stop. Rest. Breath. Repeat. Continue as long as possible, as softly as possible, rubato again, insistent once again, louder again, as loud as possible, barely breathing, start over, always fortissimo; stop. A tight tremolo, almost a trill. Breathe. Modulate, calmly. Not yet. Restrain yourself. Breathe with me. Calm, almost motionless. Now: suddenly. Serrando, stringendo, let the resonance ring. Even more. By changing the direction each time. Breathe. Repeat ad libitum without changing. To the top. Pizzicato. Always connected, straight to the end. Breathe. Legatissimo. Adapt again. Pulling. Reinforcing. Always breathing. Open tremolo, very open, almost rhythmic. Growing. Detached, almost staccato, as precise as possible, an accent on each, on time, in time, always on the downbeat. Rest. Now on the upbeat. Staccatissimo. As fast as possible. Fortissimo. Even louder. Change the position each time. Still breathing. As before, syncopating, breathing; breathing in syncopation, the off-beat, all together. Ossia. Solo. Very softly, mouth closed, stifling every vibration, without vibrato, breathing together, motionless, immobile, tacet…

All this, written this way, and read this way…does not resemble a musical score. And yet, that’s exactly what it is like. But (…again, another but…) when the computer appeared in music publishing, something fundamental changed. Whereas on the surface the content had not changed, calligraphy essentially disappeared. The drawn line was crushed by the font; the uniqueness of each artist’s calligraphy was wiped out by a “printable” layout. In French, “font” translates to “police de caractère.” In this sense, it’s as if calligraphy is now policed! Horrible :-(

Architecture is a possible metaphor. Musical writing via the computer has transformed everything from “colorful, decorated villas” to “black and white housing projects.” The worst part, for those of us who were warmly welcomed to write on computers, was another infliction: the “undo” function. Since the appearance of the digitization of musical score editing, another phenomenon, as simple as it is superficial, began: the abuse of “ctrl-z (or “command + z” on a Mac)” which allows you to “undo” an operation. The opportunity to change, at will, a passage that has just been written trivializes the present moment. While music software is essential for printing and distributing scores, the act of writing has lost its unique and irreplaceable way of capturing the present. As my mentor said, “Clarity of writing, clarity of mind.” And when we compose on the computer, we can be sure that the writing is clear (imposed by the “font police”), but there is also anonymity of the mind. Whereas with musical calligraphy (which I sometimes refer to as “identi-graphy”), there is simultaneously clarity of writing, clarity of mind, and – thanks to the uniqueness of each person’s writing – a unique artistic identity.

I searched for answers to these questions for a long time: how to reclaim the balance between writing, extreme concentration, expectations, renunciation of the intrusive “undo,” and how to give more space to the expansion of the present. In my research, I have come to understand that the expansion of the present is life itself. The living body is an expansion of the present moment. The living organism breathes, moves, evolves, and adapts. It changes, matures, ages, transforms, and metamorphoses, and every phenomenon the body experiences leaves its mark. The body is both the living, and the physical memory of the living. As in life, sometimes there are bumps, wrinkles, scars.

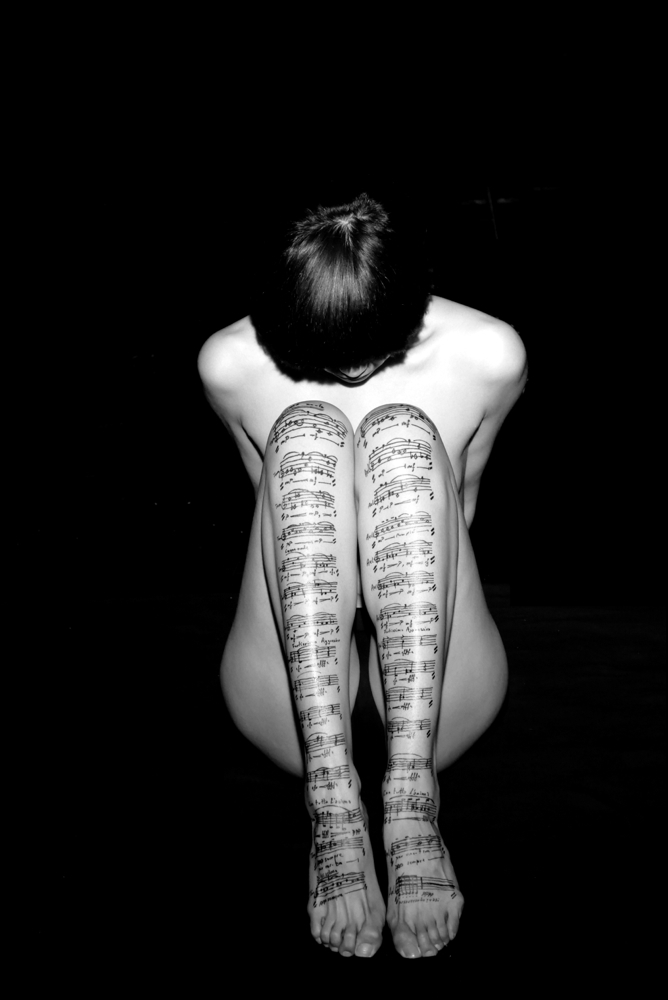

A body that breathes along with me inevitably magnifies the very moment we share. And if the body is nude, a sensual link is established. Because a man’s or woman’s nudity always implies intimacy. I have been writing scores on human bodies since 2007. At first, these were experiments, but they have since transformed into a new compositional practice. I write my works directly on human skin. Men and women come to my studio so that I may write on them. The nudity, the skin, its porosity and proximity have the explicit sensation of closeness, of being in contact; one can almost hear the breath. I write by hand, in ink. But, the canvas – the human body – is far from ephemeral, and I cannot “undo” what I write. Correction is eradicated. Mistakes must be taken into account, without exception. The vitality of the writing process is preserved by the inability to correct and by the sacredness of the presence of the naked models. Since 2013, all my works exist only through sketches written on men’s and women’s bodies. The only relics of the work are the photos that are transcribed as scores on a computer.

Yes, I know, I know. You might say, “So…in the end, the finalized score is transcribed and printed using a computer?” My reply is, “Yes”. But I also send photos of the composition sessions to the musicians. They can observe the work’s evolution, in each stage. Some musicians have even asked me to write on their bodies because they wanted to be part of the process of reclaiming the present. Most of all, in writing on the body, I have rediscovered the nuances of writing and calligraphy. I have rediscovered, via this new practice, the excellence which I had gained, then lost. The models’ nudity and participation is indeed “sacred,” as the writing sessions last between 6 and 12 consecutive hours, without interruption. There is no room for distraction, rest, or inconveniences. This new practice could be called “Breathing Together.” Because while I draw the lines, symbols, notes, and markings of the scores on the body, the model breathes with me, in the same tempo and rhythm. The model remains immobile, so that the ink lines remain pure, clean, and precise. I have transcended the very notion of writing as performance: as with all performance, distraction, dispersal, and errors are anathema.

There are countless photographs of musicians: singers, violinists, pianists, percussionists, guitarists, or conductors. Their faces, facial expressions, their tense bodies… Or the musical instruments, with or without the musicians. It may seem that nothing new can exist in the relationship between music and photography. But despite this, one questions remains unanswered: what are these musicians playing? Is it possible to take into account, via photography, the deepest nature of music, its composition?

I was inspired by several cinematic masterpieces, including Kenji Mizoguchi’s Utamaro and His Five Women and Peter Greenaway’s The Pillow Book because the Body Scores project recounts the relationship between the body, writing, and movement. When I compose on the bodies, everything is present. The score breathes with me. A body’s imperfections sometimes forces me to make unexpected decisions, which points to the possibility that mistakes can be fertile when the unforeseen has its place. The same space where the “undo” function, in my use of computers, was commonplace. This new practice (which I call Body Scores) traces the relationship between the body, nudity, writing, and gesture. Like temporary tattoos which dissolve with water, the only way to preserve a trace is with photography. Sometimes I take these photos myself, but I also work with other photographers. This magnifies the sacredness of the writing, as the act of writing becomes a performance, whose artefacts are the photographs.

Photos by Jacopo Baboni Schilingi

Body Scores: Reinventing the Body within the Machine

By Manuela De Barros

Today, musical scores are generated by software, which allows the musical transcriptions to be printed and distributed, directly. Therefore the “original” notation is in fact already an automated product. Before the advent of such tools, scores were handwritten by composers, and the calligraphic excellence required was part of their stringent training. As with any precise, concentrated work, writing scores by hand demands long, intense labor. With time, a composer’s handwriting becomes a style, part of their personal signature, which corresponds to their sensibility.

This is the school of composition in which Jacopo Baboni Schilingi was trained. Then, for seven years, he wrote using a computer and experienced notation in its most convenient form: the possibility of deleting errors, mistakes or inaccuracies, and the distinctly reduced remorse. He worked this way until he came to the realization that his music had changed. While the writing had gained in speed, and the mind was allowed a lower threshold of concentration, these same changes influenced the depth of the work itself.

Umberto Eco previously established the transformation of the literary act by the use of word processors. For the future researcher, linguist or philologist, the writing process and the alterations of successive versions are now irretrievably lost by the touch of a computer key, allowing for the rapid and categorical erasure of a composition’s earlier variants. In addition, the act of writing and typing are not quite the same, particularly in terms of cognitive function. Writing by hand is not only a necessary process for basic learning, but – as we now know – the gesture of writing links vision and touch; or, more precisely: the brain simulates the movement before the act of writing. Accordingly, moving the hand is not the same process as calling forth a letter (or a note) on a screen. In other words, cognitive structures are a function of physical activity. Therefore it is logical that the mechanics of writing should transform the resulting text.

The knock-on effects could be even greater for a musical score, which comprises not just notes and musical symbols, but rhythmic indications and emotions to be expressed. The score also provides guidelines for posture and movement, as well as indications for executing the score. Ultimately, it suggests a subtle choreography which allows the instrument or voice to express the composer’s intentions. As listeners, we are then “touched” by the music, which we hear as it simultaneously vibrates within us.

Hesitantly at first, in 2007, and with increasing boldness from 2013 onwards, Jacopo Baboni Schilingi modified his compositional method to rediscover a “sculptural” sensibility, which had previously been altered by machines, via living materials, indispensable for creation. His choice is drastic, emphatic and powerful, as it represents – literally – a return to the body, a carnal return: his scores are henceforth not just written by hand, but also written directly onto human bodies. In his studio, converted into both a calligraphy atelier and photography studio, he collaborates with male and female models, who serve as living canvases for his compositions. For six to twelve hours he composes, rediscovering the power of the present moment. He also fully re-experiences duration, previously wiped out by the digitization of time, and by computer-assisted composition, far from the body.

The models are naked, naturally, and their skin, which becomes the composition’s canvas, needs to have relatively few irregularities, hair, or protruding muscles. Any roughness encountered is taken into account by the composer, influencing the score, as an unforeseen element to be integrated within the final result. The implications can be far-reaching. For example, a mole may create a “accident” which fits into a musical motif, and must be repeated further along, although it had not been preconceived in the abstract. Certain body parts are more suitable for certain types of compositions;the size of the notes and staves are adjusted to the canvas. The canvas’s color is not an inherent constraint, but the lack of tools (i.e. felt-tip pens) suited to writing on very dark skin limits the possibilities for the time being.

The work therefore consists of the intersection between the model’s skin and artisanal, calligraphic techniques, and is also influenced by the postures and concentration. But the body is not merely a surface; the entire organism participates in the process. On the one hand, the composer is inspired by the body’s landscape; on the other, the body is alive, not inert like a sheet of paper. The skin encloses muscles, organs, and a skeleton. It contains a spirit which responds to emotions, which manifests itself by the breath, which can in turn be a measure of time. Breath is a source of life, always renewing itself. But it can also serve as an external indicator of an internal state. Everyone knows the feeling of intimacy between two breaths which meet, mingle, respond…or spurn one another. Jacopo Baboni Schlingi describes his concentration, which approaches self-hypnosis, and the necessity of a mimetic synchronicity between two breaths, a community of tension and release, without which the magic is broken, the music silent. It is the proximity of a trusting and respectful relationship, in which one can share intimacy without being close; moments during which one needs but few words to speak.

Sensuality is clearly present. It is as undeniable and strong as it is light and sweet, despite the sexually neutral bodies whose sexuality is nonetheless underscored. They are sometimes a bit androgynous, and the sexual organs themselves are not emphasized; on the contrary. And, while Jacopo Baboni Schilingi speaks about the composer’s “enjoyment” of the writing, it is clear that he is referring to the tranquil bliss of the radiant, noble exchange of creative elaboration.

Finally, before the last step in the process, the concert phase, he photographs each segment of the score, so that it may become part of the whole. This ensures that the ephemeral is not permanently lost, and allows the living scores to be shared with the musicians and singers who will interpret them. Following the photography, the scores are translated to paper, in a more conventional, practical form for interpretation. The photography is not a record, but the score itself. Thus, there is an original score (on the body), a master score (the photographs), and printed copies.

Even more than other scores, these scores function primarily as images for those who do not read music. The photographs of calligraphic scores on bodies share affinities with traditional calligraphic paintings by contemporary artists such as Zhang Huan and Shirin Neshat. Links are possible with other art forms: Peter Greenaway’s film The Pillow Book, Sei Shonogon’s corresponding book, and Kenji Mizoguchi’s film Utamaro and His Five Women – all initial sources of inspiration for the composer. The scores can even operate autonomously; regardless of their primary function, they also stand on their own as fully fledged works. At the same time, they are reproductions of living calligraphy, ephemeral tattoos, body paintings; they are snapshots of what was and will never again be available in its original form, records of performances without audiences or public manifestations; portraits of the participating models and the powerful relationships formed in a matter of hours. The composer takes these photographs himself, or asks photographers to take them, as when visual artists delegate the production of a work to get as close as possible to the artist’s preconceived vision.

There is a final element to consider: the apparent paradox of the freedom of inspiration sought via the body’s reconquest over the machine, from a composer who regularly uses computers in his compositions, and on stage. It is necessary to affirm once and for all that binary oppositions are unsatisfactory; they have never been fertile and can no longer prevail. Exploring a new method doesn’t mean renouncing the old. The cohabitation of bodies and machines in a rich and generous collaboration should be – on the contrary – the central element in an artistic quest, contradicting the presumed exclusion of the human in technological advancements, as is usually the case, in both design and fulfillment. This may be the most important lesson that Jacopo Baboni Schilingi shares, via his compositions’ reincarnated handwriting.

Music in your skin

By Philippe Langlois

Music is well and truly alive today. Through the various forms that it takes, so-called ‘contemporary’ music conveys in innumerable ways the dynamism and diversity of musical creation at the beginning of the 21st Century.

For composer Jacopo Schilingi, this living aspect of music is fundamental, even primordial. He concentrates on the here and now, the present, the very instant in which music is thought up, composed, where it is eventually played. He develops this very specific connection he has with living music, this ‘instantaneity’ is clear as he works on the various stages involved in composing, as he writes the score and his interpretation on stage, live. As well, he sometimes turns to digital music and processing sound in real time.

Being a composer is, above everything else, about having music ‘in your blood’, ‘in your bones’. It’s the feeling of music vibrating in your body, in an organic way, and to feel it in the very depths of your heart and soul. On the surface, you experience it as a shiver which runs all down your body, raising each goose bump, running all the way up your spine to the top of your hair, a ‘skin orgasm’ which only the emotion of music can cause.

To anchor himself even more firmly to this particular link which the composer develops with ‘living music’, specifically with its memory, Jacopo Baboni Schilingi is attempting to literally reincarnate musical writing in the here and now, a way for him to fight against the perverse effects caused by the appearance of musical production computer programmes, which have, little by little, dematerialised and disincarnated it. These programmes, which emerged around the year 2000 have been used in a generalised way and have wiped out all traces of the art of musical calligraphy. Marks, notes and traces of ink were hidden by the ‘character police’, banishing the originality of calligraphy into the forgotten past. Previously, publishing houses would have published faxes of the original manuscripts. Musical writing has a duty to raise the art of calligraphy to the highest degrees of perfection. One only has to see manuscripts of scores written by Brian Ferneyhough, Ivan Fedele, or France Donatoni who, in this field, represent meticulously perfect models of this art.

Since 2007, Jacopo Baboni Schilingi has therefore tried to take up this art again, desiring to make calligraphy continue, in a very particular and personal way; through the revival of his practice of musical writing. Touched by the cinematic adaptation of the book by Sei Shonagon, Pillow book by Peter Greenaway in 1996, as well as Cinq femmes autour d'Utamaro by Kenji Mizoguchi (1946), he slowly began to write sketches of scores directly onto bodies, onto the living skin of models. He asks them to his studio, where in slots of six to twelve hours to compose, with a thin tip felt-pen on their backs, arms, faces, legs, chests, and patiently inks staves and music notes, a way of literally ‘incarnating’ the motion of writing on the living, a way to make sacred this action in this written form. In doing this, he reaffirms his attachment to traditional writing, abandoning the ‘character police’ in favour of calligraphy, which he carries out on the smooth skin of models he invites to his studio.

There is nothing more obvious than the body for speaking the truth about life, the envelope of the living, which is the skin, this living canvas upon which the memory of the past can be read. Thanks to the pre-eminence of the motion itself, the memory of writing is coming back to life in the same moment of living and of thought. To ink music onto the skin is also seeking to anchor again the living of creation from the writing stage.

Without any possibility of deleting or going back or being able to rip up the medium, mistakes are not allowed, or rather is has to be included and accepted in the written piece of music. It can be likened to a search for the perfection of a motion, or movement, like the fable of Italo Calvino, Rapidié, taken from Leçons américaines, in which is told the story of a Chinese Emperor who orders the best artist in the kingdom to draw the best picture of a crab, and who, after ten years of working, produces in one stroke, before a dumbfounded emperor, the outline of a crab in the perfection of a motion which has been repeated over and over again.