Scarlet K18 is a new composition I'm writing for Luca Quintavalle using the Bodyscore practice.

It is a collaboration between Luca Quintavalle, the performer Agathe Vidal and myself.

Commisoned by Forberg-Schneider Stiftung http://www.forberg-schneider.de

Here you can see my last Bodyscore exhibition:

Bodyscore project exists across different kind of monstration: books of photography, photo exhibitions in art galleries or art centres, live performances during which scores are painted lively, concerts where scores are projected on stage while musicians are playing.

There are countless photographs of musicians: singers, violinists, pianists, percussionists, guitarists, or conductors. Their faces, facial expressions, their tense bodies… Or the musical instruments, with or without the musicians. It may seem that nothing new can exist in the relationship between music and photography. But despite this, one questions remains unanswered: what are these musicians playing? Is it possible to take into account, via photography, the deepest nature of music, its composition? The musical score.

The score is a codified link, written by hand, which indicates how to embody the emotions that the composer expresses through his creation.

Today, musical scores are generated by software, which allows the musical transcriptions to be printed and distributed, directly. Therefore the “original” notation is in fact already an automated product. Before the advent of such tools, scores were hand written by composers, and the calligraphic excellence required was part of their stringent training. As with any precise, concentrated work, writing scores by hand demands long, intense labor. With time, a composer’s handwriting becomes a style, part of their personal signature, which corresponds to their sensibility. This is the school of composition in which Jacopo Baboni Schilingi was trained.

Writing by hand is not only a necessary process for basic learning, but – as we now know – the gesture of writing links vision and touch; or, more precisely: the brain simulates the movement before the act of writing. Accordingly, moving the hand is not the same process as calling forth a letter (or a note) on a screen. In other words, cognitive structures are a function of physical activity. Therefore it is logical that the mechanics of writing should transform the resulting text.

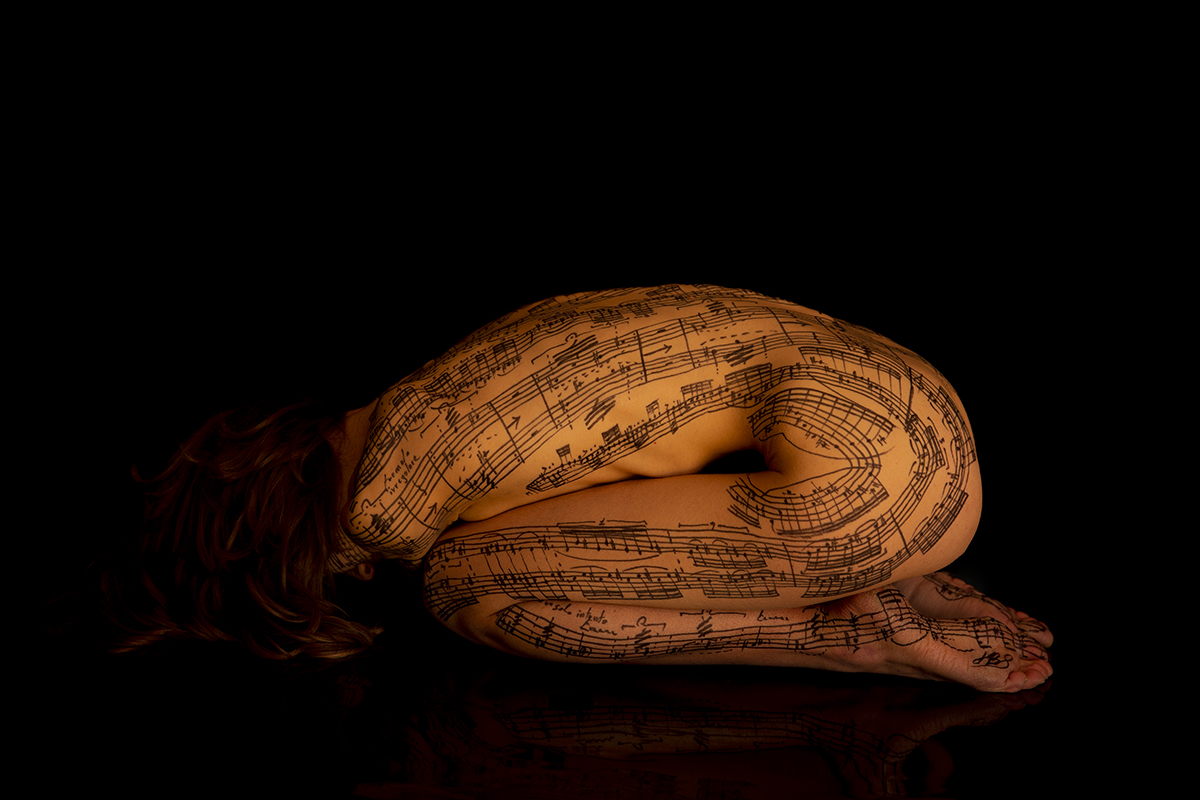

Since 2007, Jacopo Baboni Schilingi modified his compositional method to rediscover a “sculptural” sensibility, which had previously been altered by machines, via living materials, indispensable for creation. His choice is drastic, emphatic and powerful, as it represents – literally – a return to the body, a carnal return: his scores are henceforth not just written by hand, but also written directly onto human bodies. In his studio, converted into both a calligraphy atelier and photography studio, he collaborates with male and female models, who serve as living canvases for his compositions.

Body Score by Jacopo Baboni Schilingi

A few months ago, I tore up a sheet of music. The gesture had disappeared from my life and practice, for years now. For a friend’s birthday, I wanted to give him a handwritten copy of a composition he loves. But after a setback, I tore up the score. Tearing up something that you spent hours – even days – writing by hand is a brutal gesture. It is a final act. Tearing up a page leaves an indelible scar, one so deep that it becomes necessary to throw the page away. The act is violent, even theatrical.

For two years now I have asked myself fundamental questions about my work. Of course, I am a composer; I write and practice music. But I’ve been reflecting about how I go about it, via the writing process. I am becoming more and more interested in what it means to write music today, in 2015, and about the “old” way of experiencing music, via handwritten scores. Especially today, when almost everything is digital: computers, touch screens, networks, sensors…

Let’s compare the act of tearing up a sheet of music to “deleting” music from a hard drive. What a huge difference! There is nothing more ephemeral than the gesture of erasing a file from a computer. Click and delete. It’s gone! Such bravery! How heroic. Especially when we know that we can simply click “undo” to retrieve the file… Because the text displayed on the computer has not really been written. It was “typed.” Yuck! To “type a text” is not a very noble expression. Thus, I question my art. The music. Writing, composition. I belong to a generation of composers known as the “pen/mouse” generation: we know how to write for orchestra, string quartet, and voice, etc. on paper, but for concerts where electronics and information technology is ubiquitous. I compose music referred to as “mixed” and “interactive,” in which classical performers (pianists, violinists, oboists, opera singers, etc.) are on stage, and read and study music on paper, but who interact with computers during performances. This is the kind of music that I like. It suits me best. Faced with the possibilities, it is what I freely choose.

But (…and there is a but), from the age of 6 until 1999 (when I was 28), I composed by hand, on paper. The role of my publisher was limited to photocopying the scores, which needed to be written clearly enough to be read by musicians. Essentially, my publisher photocopied my manuscripts and distributed them to musicians. So I had to learn to write my music neatly, in terms of calligraphy, or it would not be played. To teach me how to write well, my mentor made me rewrite my first publically performed piece four times before delivering it to the performers. Not because of the musical content, but because of the calligraphy. I was 15. I was compelled to develop my own penmanship.

Writing changes over time. It grows with age and experience. As in any calligraphy, each gesture is the vehicle of the mood and the mental state of the artist. The score written by hand is the trace of the artist/composer, who is expressing himself; beyond the musical content, the score manifests the emotional state of the composer. Up until 1999, scores needed to be handwritten well so they could be read and performed live. The term speaks for itself: musical calligraphy. Beautiful music-writing. When writing by hand, it is necessary to be very focused to ensure the quality of the work and the visual quality within a given format. My teacher always told me, “Clarity of writing [reflects] clarity of mind.” Therefore, expectations were high. When writing by hand, an error, a crossing-out, an erasure, or starting over all cost a lot of time. Therefore we focus intently, so that even if mistakes can happen, we aspire to remain in the creative flow for hours at a time. It is a kind of psychic extension of being fully in the present, which the artist/composer knows so well. A state of concentration approaching trance, autohypnosis. Nothing exists but the music surrounding the artist. Time is suspended, but not in the way people often think. It is a time so accelerated that it seems as if the composer is paralyzed. In the pure enjoyment of the act of writing the sound, the artist/composer finds himself composing for hours without perceiving effort, fatigue, or any other concerns other than the writing itself. Because there is only the mental simulation of the music that will be played. A form of pleasure in preview, which only the composer knows, prepares, and plans.

Since the advent of music notation, scores have always aroused the utmost respect in musicians and non-musicians alike. Because for musicians the written score produces a sense in itself (a musical sense); for non-musicians the score represents the complex link between the imagination of an aural idea and the expression of this idea through others (performers), before they have even read the music. For non-musicians, the musical score is a kind of indecipherable letter, teeming with secrets. They are written, stripped bare, and yet unreadable. And while remaining indecipherable to non-musicians, the score is immediately recognizable as music by everyone, including those who don’t know how to read it. The score is the privileged medium between composer and interpreter.

The score is a codified link, written by hand, which indicates how to embody the emotions that the composer expresses through his creation. In his imagined potential; in his life; in his utopian possibility of existence: communication. And at the same time, through the only concrete reality of existence: music.

Of course, within a score we write notes and many other symbols, and these are the musician’s instructions. But a score is even more: it is a physical body on which the composer writes by hand, corrects, highlights, and erases, leaving all kinds of traces. At the same time, the score must be incomplete enough so that the performers can complete it with their own intentions and interpretations. And each interpreter – on the same score – adds new signs and symbols that will help them adapt to the composer’s intentions.

The score is the medium in which the interpreter can read the composer’s emotions, codified in the form of musical writing. Thus, the emotions of the composer are entrusted to the performers so they can relay them to the public via their musical instruments’ gestures. In a score, there are not just musical notes; for the musicians, these symbols imply hand, mouth and lip positions, feet movements, ways to use their bodies, and ways to move with the score’s aforementioned instructions.

A sensual relationship is undeniably established.

Movements, breathing, hesitations, uncertainties, impulses, efforts, tensions, relaxations, breathing, more breathing, how to breath, how to move, when to stay still. Softly, unhurried, crescendo, accelerando, pause. Breathe. Repeat from the beginning, slow down; stop. Rest. Breath. Repeat. Continue as long as possible, as softly as possible, rubato again, insistent once again, louder again, as loud as possible, barely breathing, start over, always fortissimo; stop. A tight tremolo, almost a trill. Breathe. Modulate, calmly. Not yet. Restrain yourself. Breathe with me. Calm, almost motionless. Now: suddenly. Serrando, stringendo, let the resonance ring. Even more. By changing the direction each time. Breathe. Repeat ad libitum without changing. To the top. Pizzicato. Always connected, straight to the end. Breathe. Legatissimo. Adapt again. Pulling. Reinforcing. Always breathing. Open tremolo, very open, almost rhythmic. Growing. Detached, almost staccato, as precise as possible, an accent on each, on time, in time, always on the downbeat. Rest. Now on the upbeat. Staccatissimo. As fast as possible. Fortissimo. Even louder. Change the position each time. Still breathing. As before, syncopating, breathing; breathing in syncopation, the off-beat, all together. Ossia. Solo. Very softly, mouth closed, stifling every vibration, without vibrato, breathing together, motionless, immobile, tacet…

All this, written this way, and read this way…does not resemble a musical score. And yet, that’s exactly what it is like. But (…again, another but…) when the computer appeared in music publishing, something fundamental changed. Whereas on the surface the content had not changed, calligraphy essentially disappeared. The drawn line was crushed by the font; the uniqueness of each artist’s calligraphy was wiped out by a “printable” layout. In French, “font” translates to “police de caractère.” In this sense, it’s as if calligraphy is now policed! Horrible :-(

Architecture is a possible metaphor. Musical writing via the computer has transformed everything from “colorful, decorated villas” to “black and white housing projects.” The worst part, for those of us who were warmly welcomed to write on computers, was another infliction: the “undo” function. Since the appearance of the digitization of musical score editing, another phenomenon, as simple as it is superficial, began: the abuse of “ctrl-z (or “command + z” on a Mac)” which allows you to “undo” an operation. The opportunity to change, at will, a passage that has just been written trivializes the present moment. While music software is essential for printing and distributing scores, the act of writing has lost its unique and irreplaceable way of capturing the present. As my mentor said, “Clarity of writing, clarity of mind.” And when we compose on the computer, we can be sure that the writing is clear (imposed by the “font police”), but there is also anonymity of the mind. Whereas with musical calligraphy (which I sometimes refer to as “identi-graphy”), there is simultaneously clarity of writing, clarity of mind, and – thanks to the uniqueness of each person’s writing – a unique artistic identity.

I searched for answers to these questions for a long time: how to reclaim the balance between writing, extreme concentration, expectations, renunciation of the intrusive “undo,” and how to give more space to the expansion of the present. In my research, I have come to understand that the expansion of the present is life itself. The living body is an expansion of the present moment. The living organism breathes, moves, evolves, and adapts. It changes, matures, ages, transforms, and metamorphoses, and every phenomenon the body experiences leaves its mark. The body is both the living, and the physical memory of the living. As in life, sometimes there are bumps, wrinkles, scars.

A body that breathes along with me inevitably magnifies the very moment we share. And if the body is nude, a sensual link is established. Because a man’s or woman’s nudity always implies intimacy. I have been writing scores on human bodies since 2007. At first, these were experiments, but they have since transformed into a new compositional practice. I write my works directly on human skin. Men and women come to my studio so that I may write on them. The nudity, the skin, its porosity and proximity have the explicit sensation of closeness, of being in contact; one can almost hear the breath. I write by hand, in ink. But, the canvas – the human body – is far from ephemeral, and I cannot “undo” what I write. Correction is eradicated. Mistakes must be taken into account, without exception. The vitality of the writing process is preserved by the inability to correct and by the sacredness of the presence of the naked models. Since 2013, all my works exist only through sketches written on men’s and women’s bodies. The only relics of the work are the photos that are transcribed as scores on a computer.

Yes, I know, I know. You might say, “So…in the end, the finalized score is transcribed and printed using a computer?” My reply is, “Yes”. But I also send photos of the composition sessions to the musicians. They can observe the work’s evolution, in each stage. Some musicians have even asked me to write on their bodies because they wanted to be part of the process of reclaiming the present. Most of all, in writing on the body, I have rediscovered the nuances of writing and calligraphy. I have rediscovered, via this new practice, the excellence which I had gained, then lost. The models’ nudity and participation is indeed “sacred,” as the writing sessions last between 6 and 12 consecutive hours, without interruption. There is no room for distraction, rest, or inconveniences. This new practice could be called “Breathing Together.” Because while I draw the lines, symbols, notes, and markings of the scores on the body, the model breathes with me, in the same tempo and rhythm. The model remains immobile, so that the ink lines remain pure, clean, and precise. I have transcended the very notion of writing as performance: as with all performance, distraction, dispersal, and errors are anathema.

There are countless photographs of musicians: singers, violinists, pianists, percussionists, guitarists, or conductors. Their faces, facial expressions, their tense bodies… Or the musical instruments, with or without the musicians. It may seem that nothing new can exist in the relationship between music and photography. But despite this, one questions remains unanswered: what are these musicians playing? Is it possible to take into account, via photography, the deepest nature of music, its composition?

I was inspired by several cinematic masterpieces, including Kenji Mizoguchi’s Utamaro and His Five Women and Peter Greenaway’s The Pillow Book because the Body Scores project recounts the relationship between the body, writing, and movement. When I compose on the bodies, everything is present. The score breathes with me. A body’s imperfections sometimes forces me to make unexpected decisions, which points to the possibility that mistakes can be fertile when the unforeseen has its place. The same space where the “undo” function, in my use of computers, was commonplace. This new practice (which I call Body Scores) traces the relationship between the body, nudity, writing, and gesture. Like temporary tattoos which dissolve with water, the only way to preserve a trace is with photography. Sometimes I take these photos myself, but I also work with other photographers. This magnifies the sacredness of the writing, as the act of writing becomes a performance, whose artefacts are the photographs.